GM’s approach to big-displacement engines in the Corvette has shifted several times over the decades. In the 1960s and early 1970s, models powered by 427 and 454 cubic-inch V8s leaned heavily on size and torque to deliver performance, helping cement the Corvette’s reputation during the muscle car era.

The LS7 V8 returned to the 427-cubic-inch figure from a very different angle. Rather than revisiting the big-block formula, GM engineered the LS7 as a small-block focused on weight reduction, airflow, and durability under track conditions. Developed exclusively for the C6 Corvette Z06, it reflected a moment when naturally aspirated displacement was still seen as a viable path to high-end performance.

As the Corvette moved into the C7 generation and later the mid-engine C8, GM shifted its performance strategy toward forced induction, electrification, and high-revving engine designs, leaving the LS7 as a clear breakpoint in that evolution.

Designed Backward From the Racetrack

The LS7 V8 did not come from GM’s usual parts-bin logic. It was conceived with a single goal in mind: to power the Chevrolet Corvette Z06 as a legitimate track-focused production car. From the start, the engine was developed around sustained high-speed operation, repeated lateral loading, and the kind of durability demands that rarely shape mass-market engines.

That track-first mindset explains why the LS7 was never intended to power multiple GM vehicles. It was designed specifically for the Z06’s aluminum frame, reduced curb weight, and aerodynamic package. A conventional wet-sump oiling system was ruled out early, leading to a dry-sump setup that ensured consistent lubrication under heavy cornering. Rather than rely on forced induction, GM chose displacement as the foundation, pairing it with aggressive airflow targets and a high redline for a pushrod V8.

Why 427 Cubic Inches Still Made Sense

By the mid-2000s, forced induction was already proving its effectiveness across the performance-car landscape. GM took a different approach with the LS7. A naturally aspirated layout offered predictable throttle response, simpler thermal management, and durability under extended track use. The decision to return to 427 cubic inches was deliberate, not nostalgic. It allowed the LS7 to meet its power targets without relying on boost, while maintaining the reliability expected of a factory Corvette.

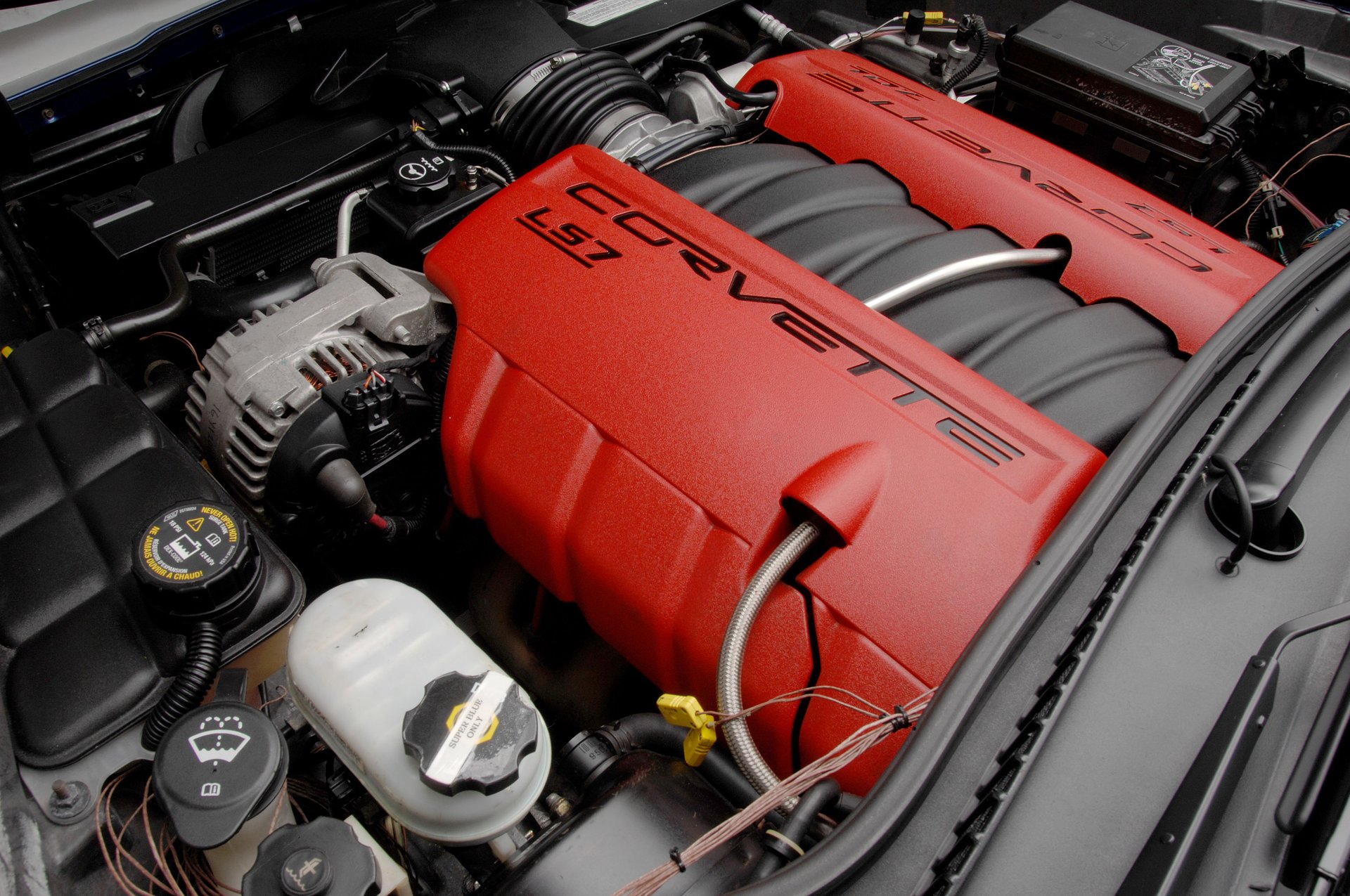

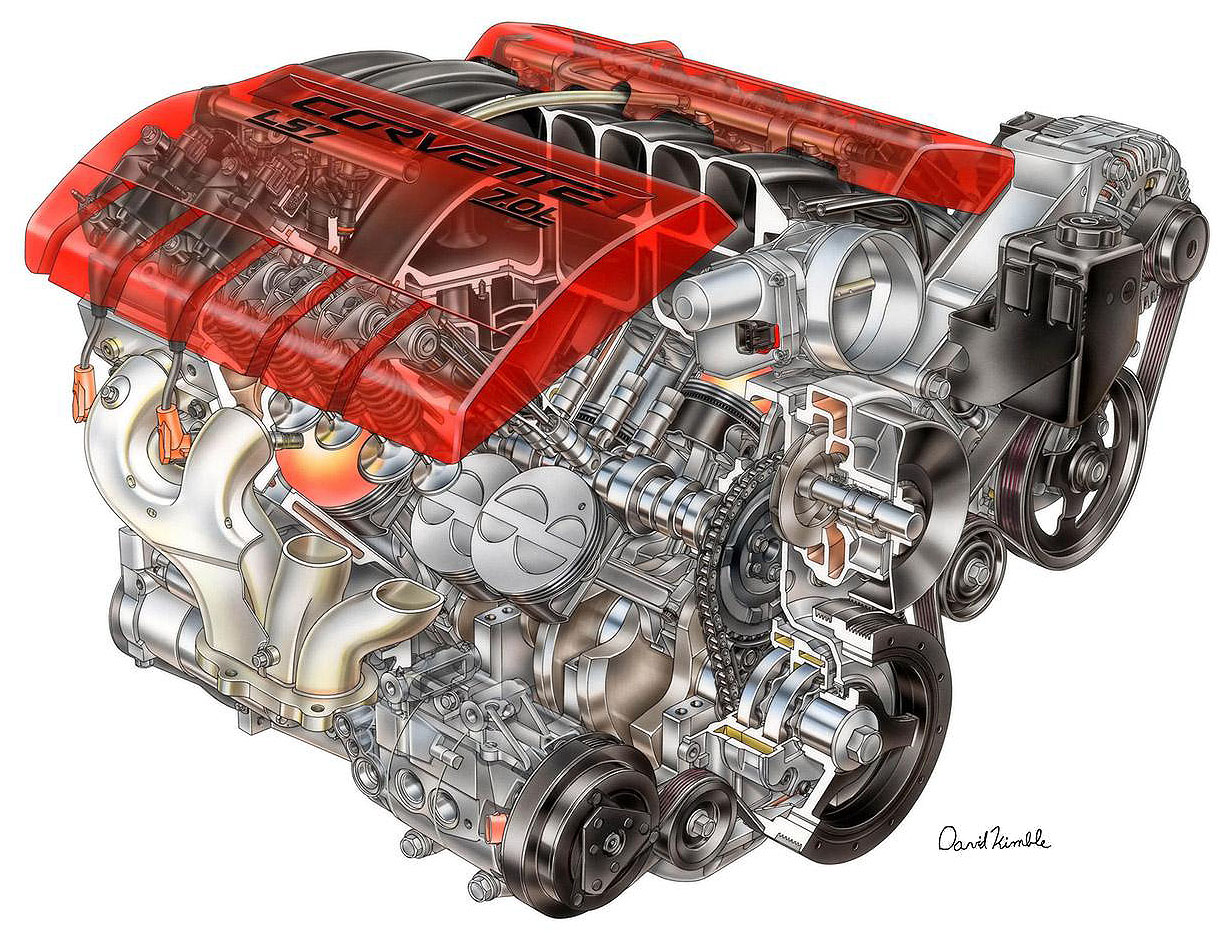

The Anatomy of GM’s Most Extreme Small-Block

While the LS7 shared the small-block label with other LS-family engines, its internal makeup set it apart. Each engine was hand-assembled at GM’s Performance Build Center, a reflection of both its complexity and limited production volume. Lightweight materials were used where they mattered most, including titanium connecting rods and intake valves, helping the engine safely operate at higher engine speeds than most large-displacement pushrod V8s.

Cylinder head design played a central role. The LS7’s heads were engineered for exceptional airflow, supporting its ability to produce over 500 horsepower without forced induction. The camshaft profile, valvetrain geometry, and bore-to-stroke ratio were all chosen to balance high-rpm capability with the low-end torque expected from a 7.0-liter engine.

Small-Block Architecture, Exotic Intent

Calling the LS7 a small-block is technically accurate, but it understates the intent behind the engine. Its size pushed the small-block architecture close to its practical limit, both in terms of displacement and mechanical stress. That ceiling is part of what made the LS7 special and also part of what made it difficult to repeat. It was never designed to scale, simplify, or evolve into a broader engine family.

A Modern 427 With Historical Parallels

The LS7’s 427-cubic-inch displacement inevitably invited comparisons to earlier Corvettes. In the late 1960s, the Corvette offered 427 big-block engines that defined the muscle car era. A few years later, displacement grew further with the introduction of the 454 big-block, which briefly became the largest engine ever fitted to a production Corvette.

Despite matching the displacement of the classic 427s, the LS7 belonged to a very different lineage. Those earlier engines prioritized straight-line power and torque, often at the expense of weight and efficiency. The LS7, by contrast, was engineered to serve as a structural and dynamic component of a balanced performance package.

For additional perspective, the current Chevrolet Corvette Z06 takes yet another approach. Its LT6 engine abandons pushrods entirely, using a flat-plane crank and dual overhead camshafts to achieve high rpm rather than large displacement.

Comparative Corvette Engine Overview

| Engine | Era | Displacement | Architecture | Aspiration | Philosophy |

| LS7 V8 (C6 Z06) | 2006–2013 | 7.0L (427 cu in) | OHV small-block | Naturally aspirated | Track durability and airflow |

| 427 Big-Block V8 | 1966–1969 | 7.0L (427 cu in) | OHV big-block | Naturally aspirated | Muscle-era torque |

| 454 Big-Block V8 | 1970–1974 | 7.4L (454 cu in) | OHV big-block | Naturally aspirated | Maximum displacement |

| LT6 V8 (C8 Z06) | 2023–present | 5.5L | DOHC small-block | Naturally aspirated | High-rpm precision |

Life Beyond the Z06 and Why GM Moved On

Although the LS7 was exclusive to the C6 Z06 in factory form, its life extended well beyond that single application. GM offered the engine as a crate motor, opening the door for independent builders, specialty manufacturers, and race teams. Companies such as Hennessey Performance adopted the LS7 for high-performance road cars, drawn by its combination of displacement and naturally aspirated response.

In motorsports, the LS7 found a home in endurance and GT-style racing applications, where its dry-sump lubrication and robust bottom end made it well-suited for sustained high-load use. Its simplicity compared to forced-induction alternatives also made it attractive to teams focused on reliability over outright peak output.

Despite its strengths, the LS7 was not a template GM could easily continue. Emissions regulations tightened, development costs rose, and warranty risk became harder to justify for an engine built so close to the limits of its architecture. GM’s performance roadmap began to diverge into separate paths.

The supercharged LS9 and later LT4 delivered higher output with less reliance on displacement. Meanwhile, naturally aspirated successors like the LT1 and LT2 prioritized efficiency and everyday usability. At the top of the range, the LT6 took a clean-sheet approach, trading displacement for rpm and abandoning pushrods altogether.

The LS7 was not discontinued because it failed to meet its goals. It was phased out because the conditions that allowed it to exist no longer aligned with GM’s broader performance strategy. In that sense, it remains a singular moment in Corvette history, one where displacement, simplicity, and track intent briefly converged before the company moved on to new solutions.