1973 XP-895 Reynolds Aluminum Corvette Concept

This article first appeared in Motortrend.com

During his tenure as the general manager of Chevrolet, John Z. DeLorean always seemed to have his eye fixed on something over the horizon. After the Corvette XP-882 mid-engine prototype chassis improvements were approved (the 882 would morph into the XP-895), DeLorean authorized the design team headed by Bill Mitchell to create a new body for the updated prototype. Something rounder, with big wheel flares, a sugar scoop rear roof treatment, and NACA ducts on the hood.

While the final design was nice, it strayed further away from the Corvette “look,” and was actually closer in style to the Two-Rotor (XP-987 GT) mid-engine Corvette prototype. Oddly, the body was mostly made of steel and the car weighed about 3,500 pounds all in—about 100 pounds more than that of a production ’73 Corvette. This would yield no performance improvement at all, so what was the point? It needed to be lighter. It needed to be a car like the Reynolds Aluminum Corvette Prototype.

Reynolds Metals (of aluminum-foil fame) had an agreement with GM since 1957 to supply GM the aluminum alloy for Corvair engines, as well as other specialty parts, many of which went into the Corvette: intake manifold, water pump, bellhousing, transmission case, etc. Reynolds also supplied the 390 alloy with 17 percent silicone that was used for the ZL1 block, L88 heads, and Vega engines.

Early in 1972, DeLorean contracted with Reynolds to build a replica of the XP-895 as that project was nearing completion to see how much weight could be saved if it were made completely of aluminum. Creative Engineering had already done the fabrication work on the XP-895 and still had the tools and jigs.

The 2036-T4 aluminum Reynolds used for the car was a special alloy designed to be spotweldable. Where needed, epoxy adhesive was used along with the spotwelding. By June of 1972, the completed aluminum XP-895 was delivered to Chevrolet’s engineering team for final assembly. Because the aluminum chassis was an exact copy of the steel version, everything went together perfectly. The completed steel and aluminum cars were both painted silver and looked totally identical. Except that the Reynolds aluminum car was 38.9 percent lighter, a whopping 450 pounds!

As incredible as that sounds, there were two major problems. First was that handbuilding a one-off car isn’t the same as designing a car to be mass-produced. However, aluminum-alloy forming and joining techniques were worked out, not unlike 20 years before when Chevrolet technicians worked out how to use fiberglass. The second major problem was the killer—cost. No matter how the numbers were crunched or if the car was built domestically or overseas, an aluminum Corvette would cost a LOT more than a steel-frame, fiberglass-body car. Not much more was disclosed, but essentially, the concept was dead and the XP-895 was put into storage.

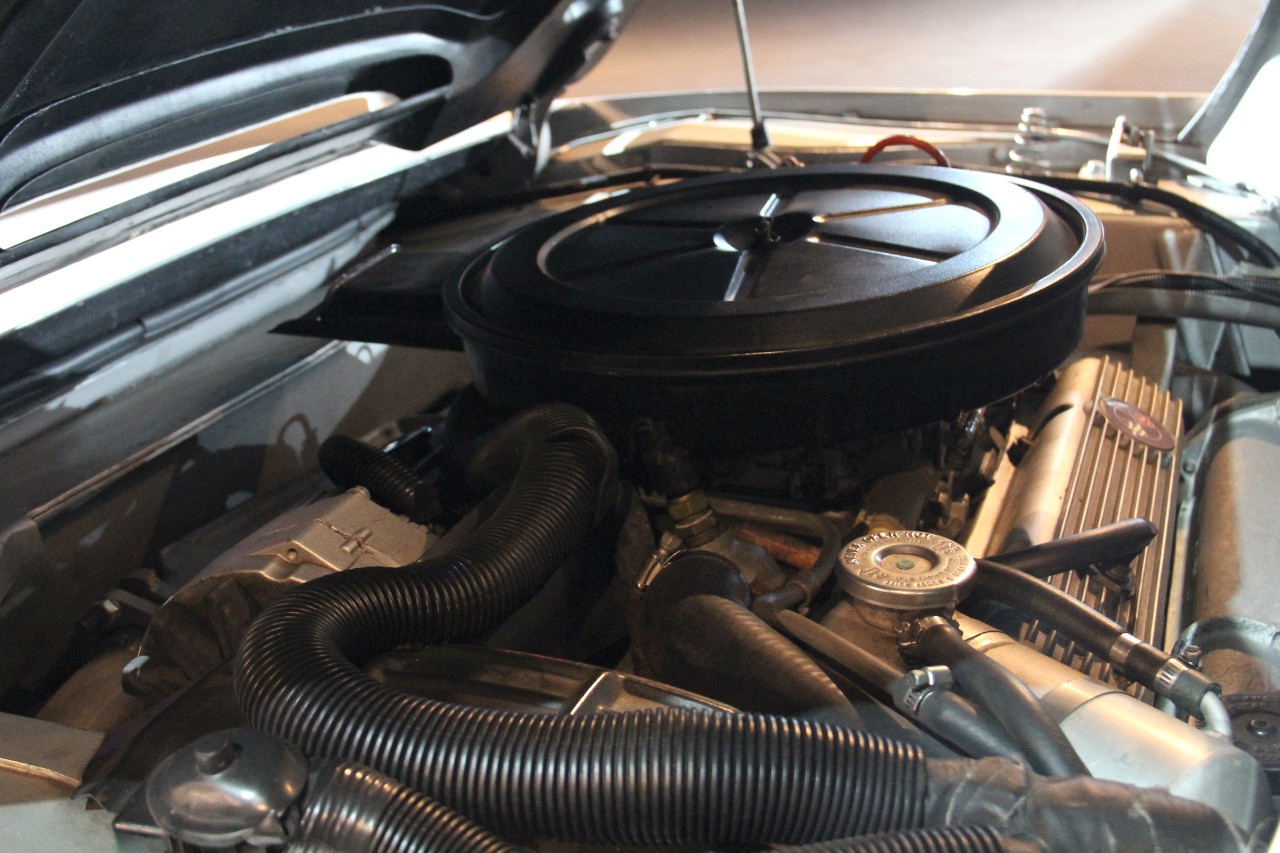

After Zora Arkus-Duntov retired from GM, Dave McLellan became the second Corvette chief engineer in 1975. Several years later, McLellan was reviewing Chevrolet’s past mid-engine Corvette cars and learned that the Reynolds Aluminum XP-895 was drivable and had it rebuilt. The car is powered by a 400-cubic-inch small block V-8 mounted transversely mated to a Turbo Hydramatic transmission via a bevel gearbox. He reported that while the ride was surprisingly soft, it felt heavy and lumbering. The interior was cramped and the “trunk” had enough room for two gym bags (just like the Fiero). However, what no one dreamed back in the ’70s was that 40-plus years later, the base model, mass-produced C7 Corvette would ride on a super strong, all-aluminum chassis—or that a mid-engine Corvette would finally become production reality as the C8.