Frank Winchell wasn’t like the extroverted Zora Arkus-Duntov; he was a typical mechanical engineer of his day—quiet but demanding. People said you didn’t work “with” Frank; you worked “for” Mr. Winchell. If an engineer told him something couldn’t be done, he’d chew them out and find someone who would do it.

For a man with no formal engineering education, he was a real Renaissance figure. Winchell headed Chevrolet’s R&D department from 1959 to 1966, and upper management loved his ability to get results. He retired in 1982 at age 65 as GM’s vice president of engineering.

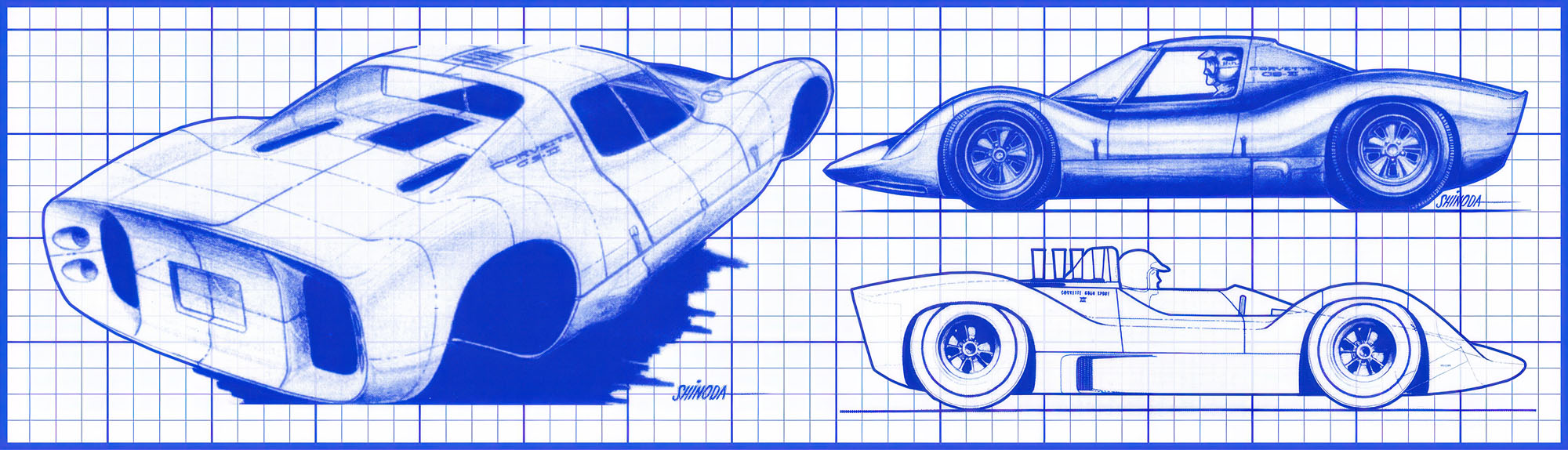

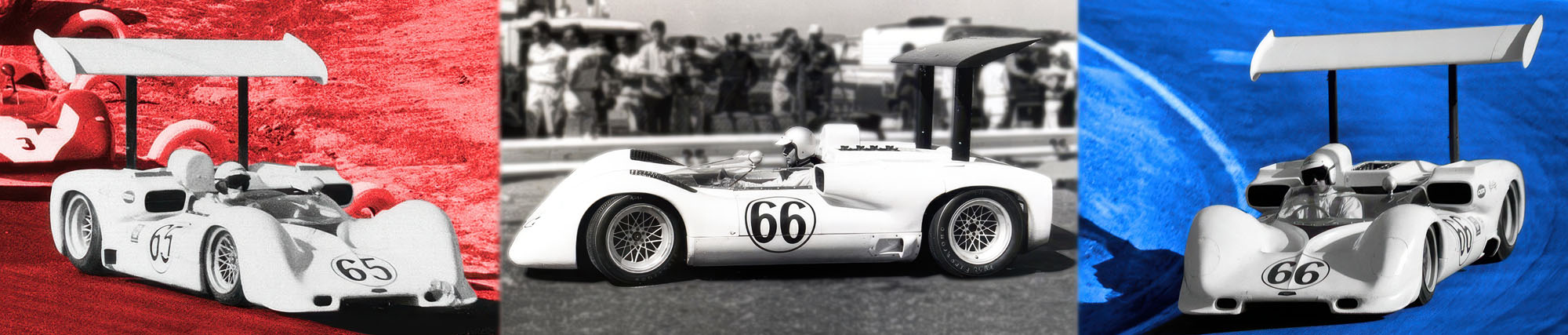

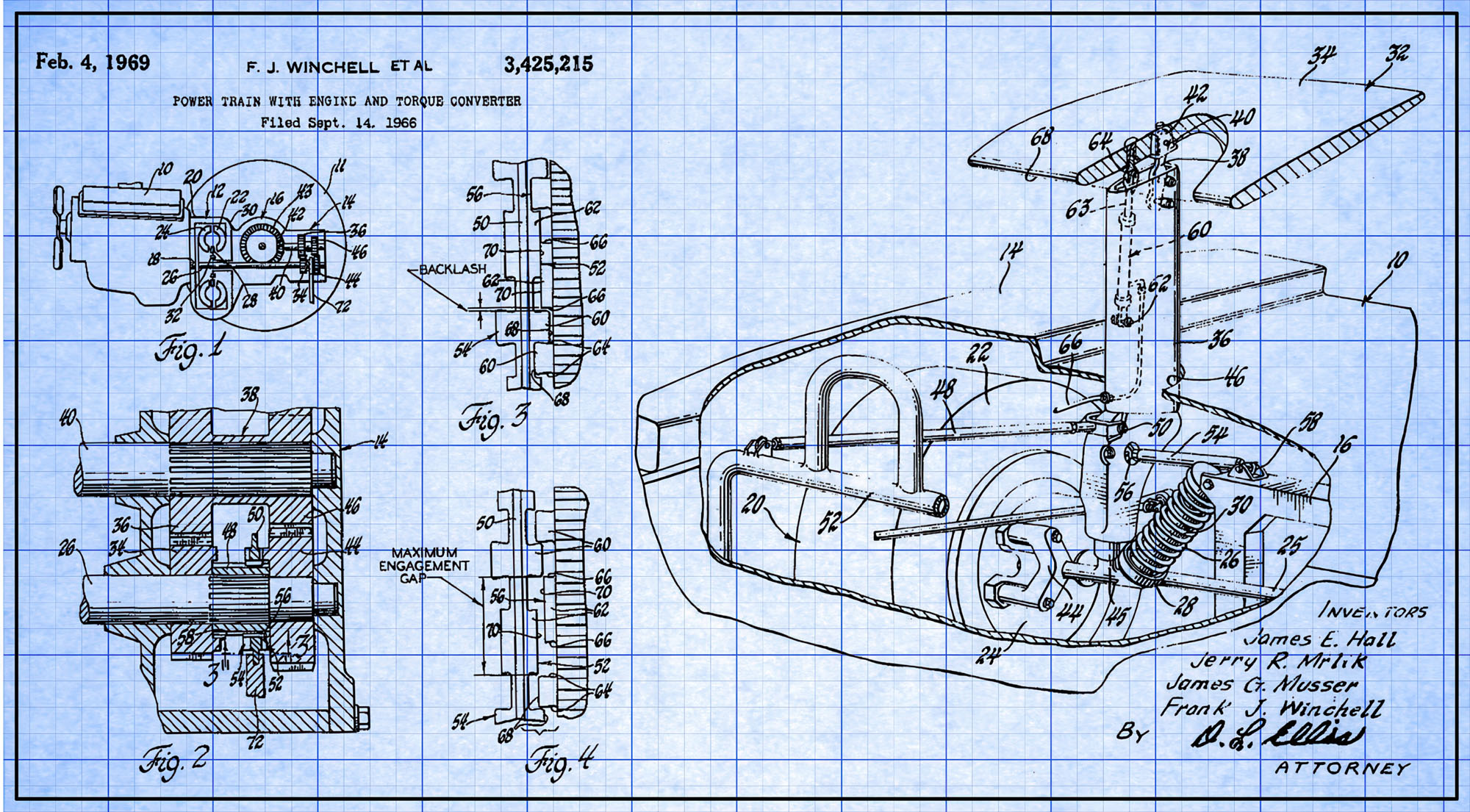

Winchell cared about pure engineering. That mindset led him to partner with young Texas oilman and racer Jim Hall, gaining 24/7 access to Hall’s private Rattlesnake Raceway in Midland, Texas—well away from the press. Hall’s early race cars were Chevy R&D machines wearing Chaparral badges. They featured mid-engine layouts, racing-grade 2-speed automatics, all-aluminum SBC engines, monocoque construction, and Larry Shinoda-designed bodies. Hall soon developed the adjustable rear wing for the Chaparral 2E, a big leap in 1964.

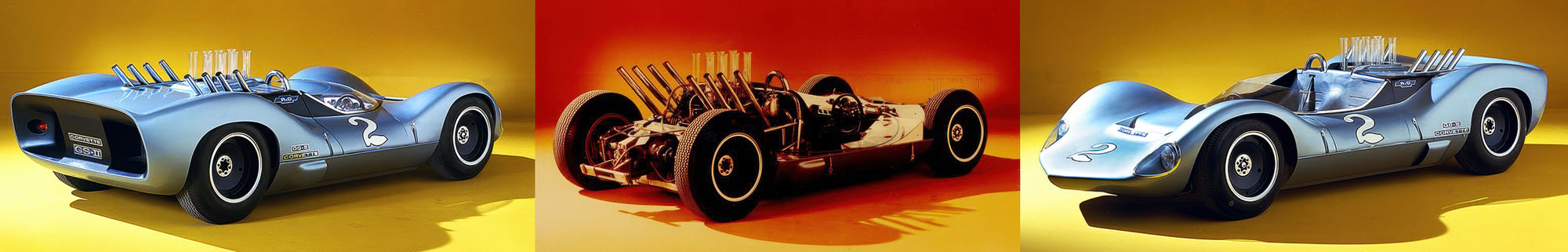

Winchell wasn’t especially interested in racing for its own sake. The private test track was also ideal for studying the lawsuit-plagued Corvair. Winchell liked the rear-engine platform, which inspired the XP-819 Corvette, featuring a small-block engine hanging off the rear axle. He believed the right suspension and tire setup would deliver excellent handling.

Duntov wasn’t thrilled with Winchell meddling in Corvette concepts. Shinoda was already working on a body that Duntov said would be an “ugly duckling.” But when he saw the full-size tape drawing, he reportedly asked, “Larry, where did you cheat?”

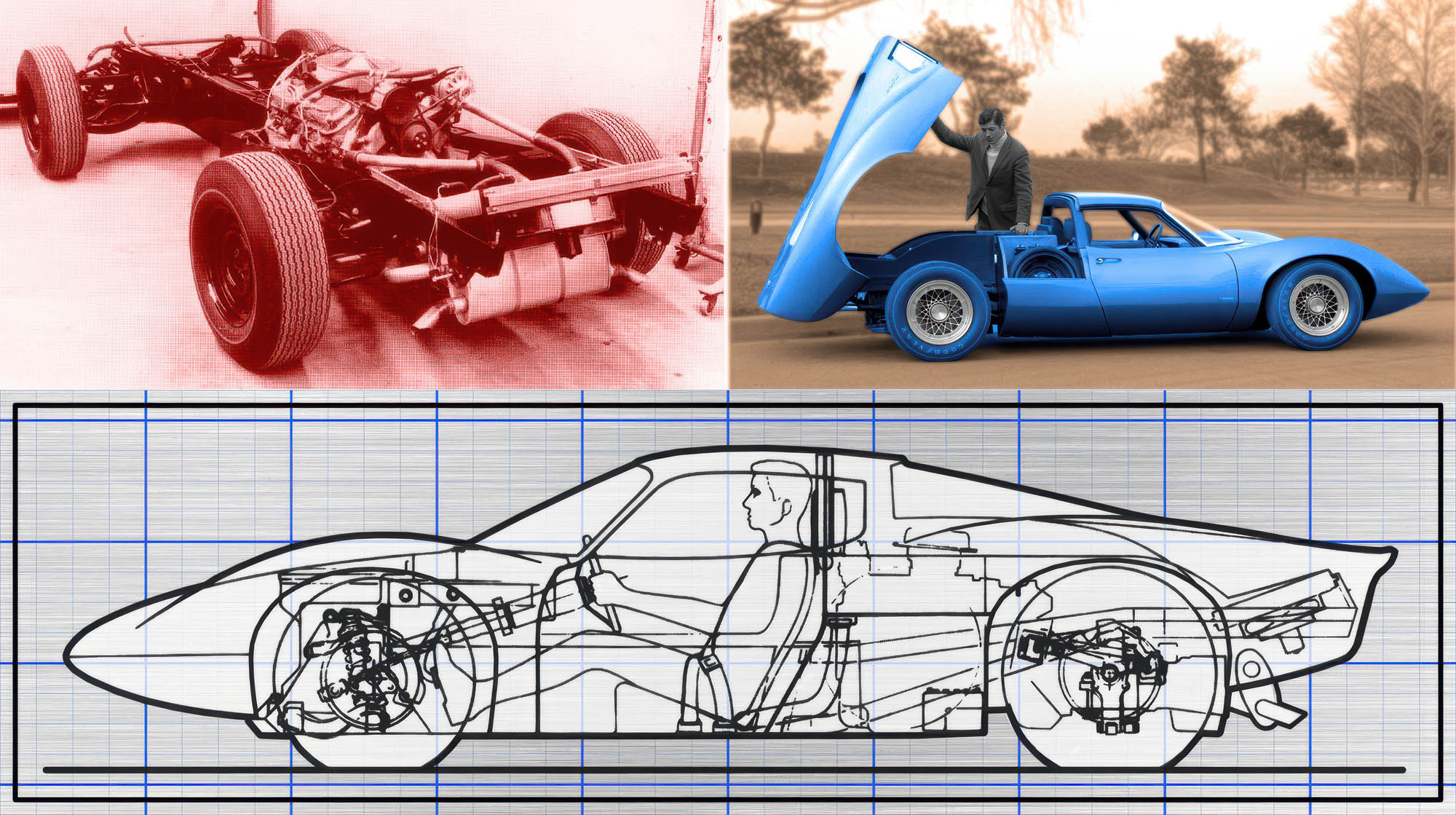

The XP-819 worked—sort of. Its rear-biased weight and wide tires held the skidpad well until the tires broke loose, and then it snapped out of control. After a crash, the car was cut apart and sent to Smokey Yunick’s garage, where it sat for years before being rediscovered, purchased, and restored at Kevin Mackay’s Corvette Repair shop on Long Island.

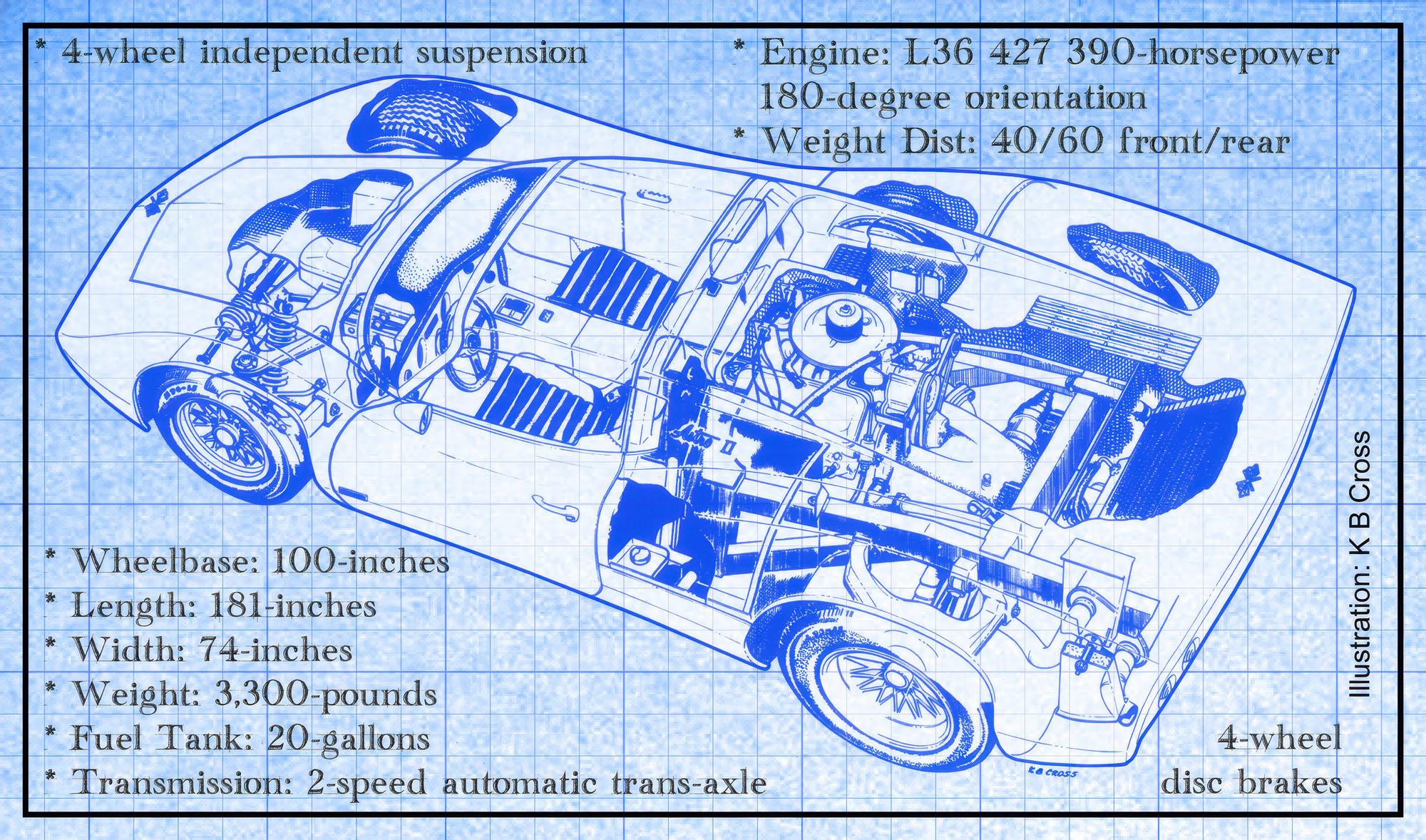

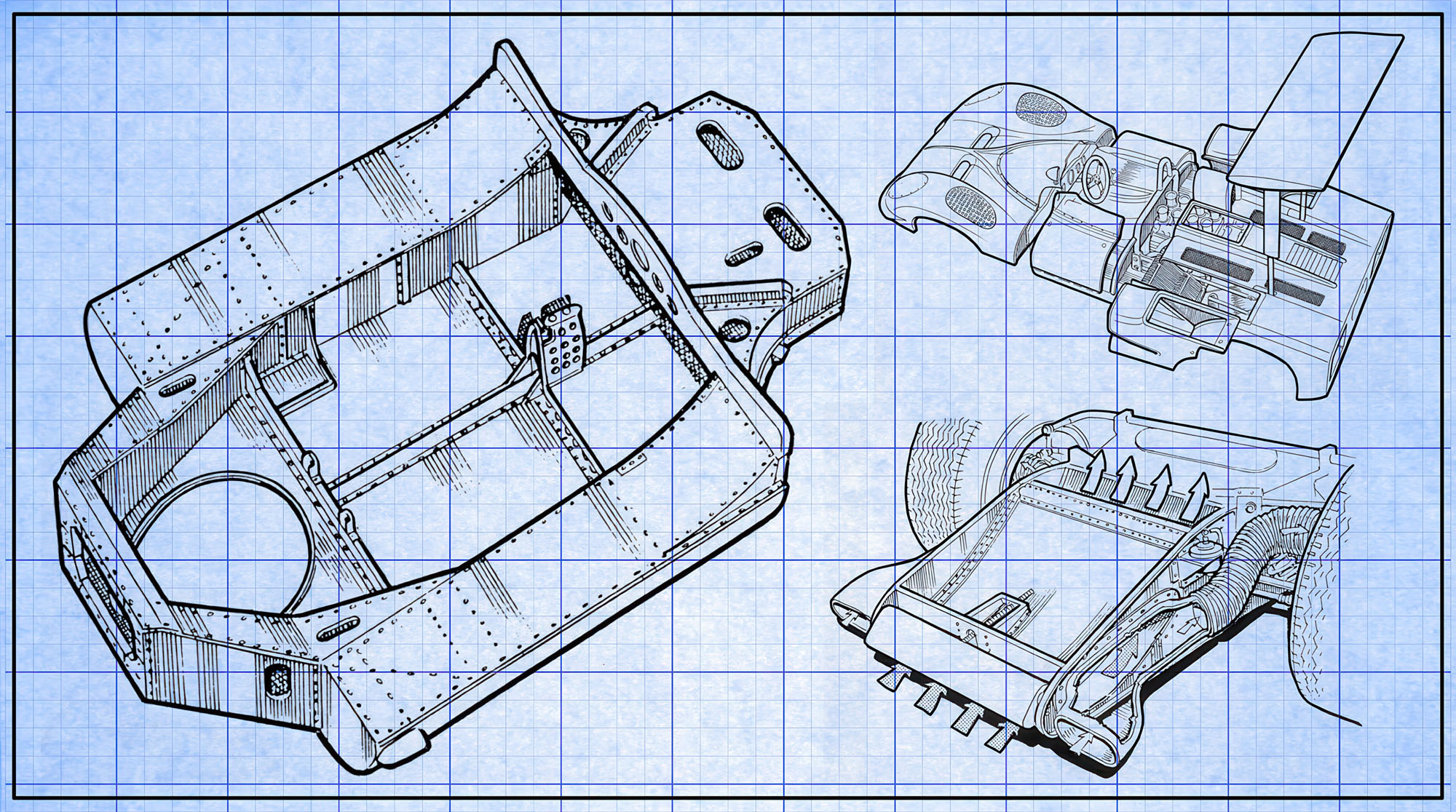

Unlike the XP-819, the 1968 XP-880 “Astro-II” was a much more realistic R&D car. The L36 427/390 sat ahead of the rear axle and was rotated 180 degrees so accessories hung off the back. The aluminum radiator was mounted behind the transaxle and fed by deck-mounted intakes. A steel backbone frame—somewhat like the later C5—held a 20-gallon fuel bladder. Suspension and brakes borrowed Camaro and Corvette pieces, with fabricated upper wishbones and coilovers. Rack-and-pinion steering sat low in front, and the antiroll bars were mounted above the suspension.

Out back, a large upper wishbone managed thrust and brake torque, and a Corvette transverse leaf spring was used. The half-shafts used Olds Toronado U-joints, and the two-speed Tempest automatic transaxle was the weak link.

Stylists made the XP-880 look convincingly like a Corvette. The roof hinted at the new C3, and the fender humps sealed the deal. Unlike the ’67 Corvair-based Astro-I, the Astro-II showed real promise in early testing, despite the very slow 23.6:1 steering. It wasn’t perfect, but it was close. For the 1968 New York International Auto Show, the Fire Frost Blue Astro-II was dressed with badges and trim, looking nearly production-ready. The press said it upstaged Ford’s Mach II.

In the end, the concept was rejected for three reasons: high tooling costs, the expense of the brand-new 1968 C3 redesign, and the strong sales of the ’68 Corvette—28,566 units. Chevrolet wasn’t about to fix what wasn’t broken.

While Winchell worked closely with Hall and explored mid-engine Corvettes, he wasn’t a racing enthusiast like Duntov. In 1967, he even proposed ending all back-door racing in favor of a Mercedes-style, engineering-driven Formula I program. Years later, Chevy did successfully build IndyCar engines. Seeing the shift to small, efficient cars, Winchell pushed for GM to build a better BMC Mini. Instead, Chevrolet chose the Vega. After a night of drinking, Winchell famously called it a “… really shitty little car.”

For all his accomplishments, Winchell carried a bit of an inferiority complex, likely tied to his lack of formal training. He once told Car and Driver publisher David E. Davis, “Well, I’m not like you. You come down here and immediately know all these Indians by their first names… You could stand on top of a car and give a speech in a goddamn gas station. I can’t do that. Every time I walk into a room, I expect somebody to ask, ‘Who’s that dumb bastard that just walked in?’”

At the Corvair Society of America at the club’s annual convention in 1979 in Detroit, Winchell said, “Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. It is indeed a pleasure to be here this evening. Everybody always says that… I’ve said it myself. But tonight is different… I mean it! First, we are here to celebrate a nice little car that we both admire, and second, while I have had many occasions to speak on the Corvair, this is the first to a friendly audience.

As a matter of fact, I have addressed very few friendly audiences… period. I don’t address anyone if I don’t have to. I don’t like speaking. I’m not very good at it, it makes me nervous, nobody pays attention, and I’m inclined to be a little profane. In fact, I don’t hardly like anyone anymore, anyway—if you want to know… I’m mad.”

GM ultimately faced 294 lawsuits and over 100 million dollars in payouts. Despite Winchell’s engineering defense of the Corvair.

The number one reason it took so long for a mid-engine production Corvette was the car’s sales success. By 1979, Corvette hit its all-time sales record of 53,807 cars. The record still stands today, although in 2023, the mid-engine C8 Corvette came within 21 units of breaking the record, with 53,785 Corvettes built. Considering the decades-long practical and development cost resistance to the mid-engine layout. This was an extraordinary accomplishment.