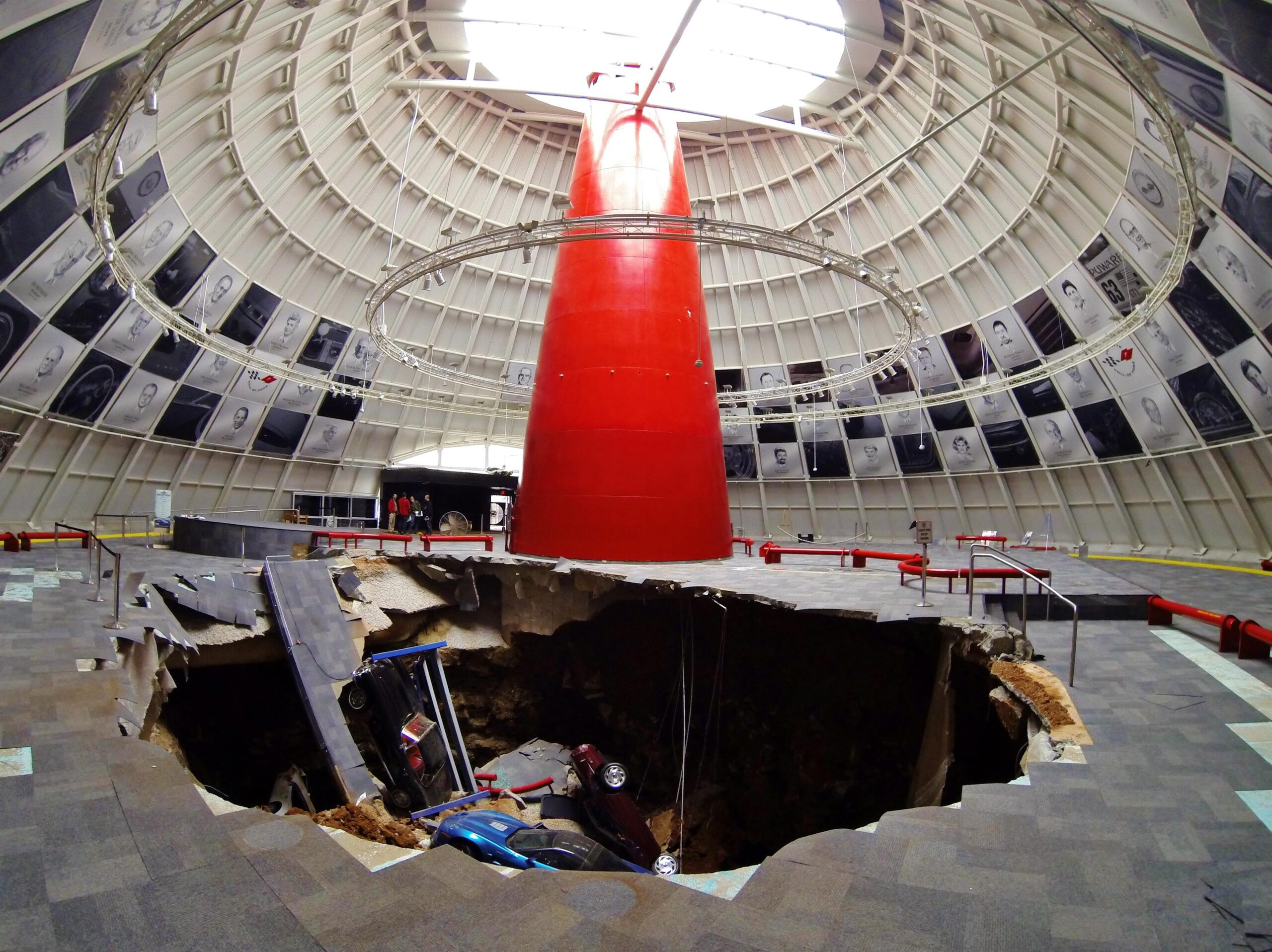

At 5:38 a.m. on February 12, 2014, the National Corvette Museum’s Skydome in Bowling Green did something no Corvette fan could have imagined: it failed. Not with a crack in the drywall or a harmless settling line—this was a full-on collapse. A massive sinkhole opened under the iconic dome and swallowed eight Corvettes, dropping them roughly 30 feet into a previously unknown cave system below.

Fortunately, the museum was closed when it happened, which meant nobody was hurt. But the footage—security-camera video that looked like it belonged in a disaster film—hit the morning news and spread like wildfire. The Skydome, which had been designed as a kind of shrine to the marque, suddenly became the stage for Corvette history’s most surreal headline.

This is the story of what happened, what it took to recover and rebuild, and what became of each of the eight cars that fell into the earth.

The Sinkhole: A Corvette Cathedral Built Over Karst Country

Recovery: Getting the Cars Out Without Making the Hole Worse

If you’ve ever watched a vehicle extraction on a trail or a crane recovery at a road course, you know the cardinal rule: don’t make it worse. One wrong pull angle, one unstable anchor point, and suddenly you’re not recovering a vehicle—you’re compounding the damage. That same logic governed every decision inside the Skydome. This wasn’t just about lifting cars out of a hole. It was about stabilizing compromised ground, reinforcing a structure that had just failed, and working methodically enough to ensure the collapse didn’t expand under the weight of cranes and crews.

Engineers studied the cavity. The floor perimeter was shored up. Recovery points were planned, re-planned, and triple-checked. Each car had to be rigged individually, carefully balanced, and slowly lifted through an opening that looked more like an excavation site than a museum floor. There was no rush. There couldn’t be.

By March 2014, the first cars began to emerge. And the one that set the emotional tone for everything that followed was the 2009 Corvette ZR1 “Blue Devil.” It was the first car extracted from the sinkhole—bruised, battered, but unmistakably intact in its identity. What happened next is the detail that Corvette people will never forget: once it was back on level ground, the ZR1 was started. And not just started—it was driven across the Skydome floor under its own power before a fluid leak prompted the team to shut it down.

Let that sink in. A 638-horsepower supercharged flagship had just survived a 30-foot fall into a limestone void—and it still fired up. If ever there were a metaphor for Corvette stubbornness, that was it. Even the earth opening beneath it couldn’t silence the thing.

The recoveries continued through March and into April. Each lift felt heavier than the last—not just in pounds, but in symbolism. Twisted frames, shattered glass, carbon fiber fractured like porcelain. And then there was the final extraction: the 2001 Mallett Hammer Z06, the most violently contorted of the group and the last to come out in April after weeks of painstaking work. It had taken the brunt of the collapse and looked like it. Bringing it back to the surface wasn’t triumphant—it was solemn. The visual proof of what gravity and limestone can do when they decide to collaborate.

And then there was a small, almost poetic detail that speaks to the humanity behind the machinery: the museum didn’t have to dig through debris to find ignition keys. They were stored separately. The “start” of each car was safe all along. It’s a minor logistical fact, but it reads like symbolism. The bodies may have fallen. The sheet metal may have buckled. But the spark—the literal ability to bring them back to life—was never buried.

In the days that followed, images of cranes, straps, and mangled fiberglass circulated worldwide. But so did the footage of that Blue Devil ZR1 rumbling across the Skydome floor. It was mechanical defiance. It was proof that while the sinkhole had rewritten a chapter of Corvette history, it hadn’t authored the ending.

Repair: Closing the Wound and Reopening the Skydome

Once the cars were out and the dust—literal and emotional—had settled, the museum was left staring at a question that had no simple answer: what does “fixed” look like when the floor drops into a cave? This wasn’t a cracked tile or a patch of compromised concrete you could grind down and resurface over a long weekend. Beneath the Skydome was a void that had just revealed itself in the most public way imaginable. Fixing it meant addressing the geology, the structure, and the long-term integrity of the building—not just making the room look whole again.

The solution was engineering-heavy and methodical. The cavity had to be mapped and stabilized. Structural supports were designed to redistribute weight away from the vulnerable zones. The floor system itself was rebuilt with reinforcement in mind, not just aesthetics. This was about ensuring that when visitors walked back into that rotunda, they weren’t just stepping onto polished concrete—they were standing on something reimagined, reinforced, and fundamentally safer than before.

By July 2015, the fully repaired Skydome reopened to the public. And that reopening wasn’t simply a ribbon-cutting. It was a statement: Corvette history would continue, and the National Corvette Museum would not be defined by that fateful morning in February of the previous year.

Today, the sinkhole is no longer an open wound in the center of the dome. You won’t peer over a railing into a limestone cavern. Instead, what remains is deliberate restraint. Subtle floor outlines trace the shape of the collapse. A discreet viewing hatch marks the location where the earth once gave way. It’s not dramatic. It’s not theatrical. It’s intentional.

The museum could have erased the event visually. Instead, it chose to acknowledge it—quietly. The Skydome floor is whole again, but the story is still there, embedded in the layout. Visitors stand where eight Corvettes once fell, often without realizing it until they notice the markings. And when they do, there’s a pause. Because what looks like polished museum flooring now is, in truth, a scar that was engineered into strength.

The Eight Cars: What Fell, What Was Saved, and Where They Are Now

Here’s the full roster, and the current status of each vehicle as documented by the museum and contemporaneous reporting.

1) 1992 Corvette — The One Millionth

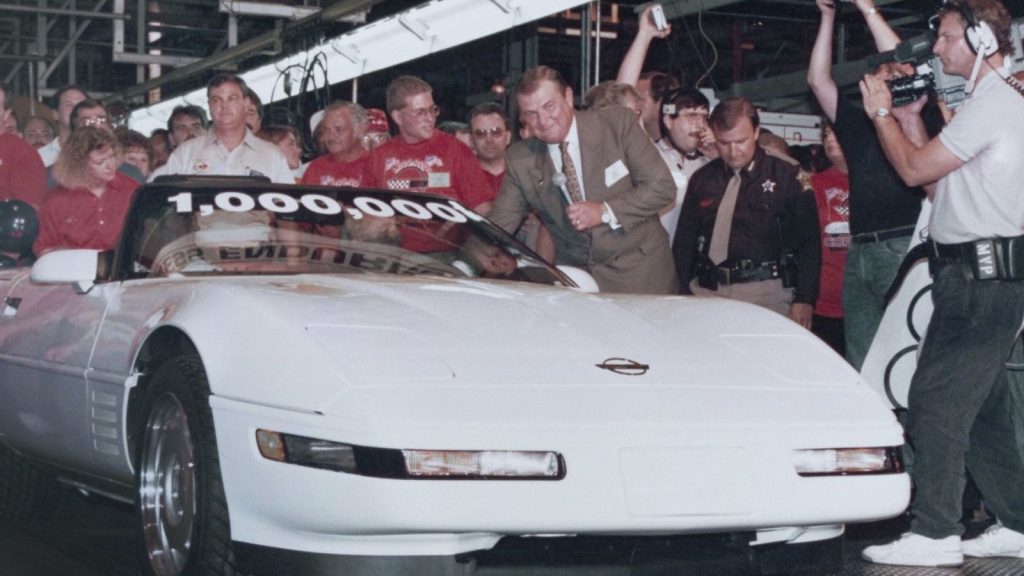

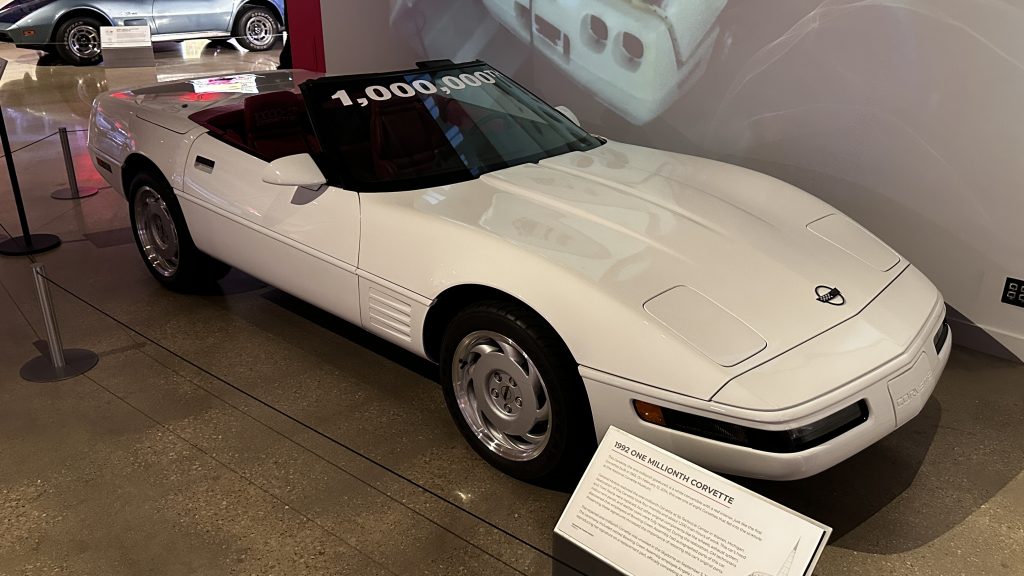

The 1,000,000th Corvette was never just another C4 rolling off the line. Built on July 2, 1992, finished in white with a red interior as a deliberate nod to 1953, it was a ceremonial milestone—an exclamation point on four decades of American sports car production. Chevrolet marked the moment publicly. The car wasn’t sold into private hands; it became a traveling ambassador, appearing at events and celebrations before ultimately finding a permanent home at the National Corvette Museum. In other words, this wasn’t simply inventory on display in the Skydome that morning—it was a living symbol of continuity. A production benchmark that represented every small-block start-up, every mid-year split window, every L88 legend, every ZR-1 resurgence that had come before it.

When the floor gave way, the One Millionth fell hard. Photos taken after its extraction showed extensive structural and cosmetic damage—cracked composite panels, a distorted frame, suspension components displaced in ways no assembly plant ever intended. And yet, given what the car represented, there was little debate about its fate. This was not going to become a static relic of disaster. It was going to live again.

General Motors undertook the restoration effort, approaching it with the same seriousness you would apply to a historically significant prototype. The process required far more than paint and panels; it meant returning a milestone VIN to factory-correct condition while respecting its provenance. After extensive work, the One Millionth Corvette was fully restored and publicly reintroduced—its scars erased, its symbolism intact.

Today, it stands not as a victim of the sinkhole, but as proof of resilience. A car built to commemorate a million Corvettes survived one of the most dramatic moments in Corvette history—and, fittingly, crossed another milestone: coming back from a 30-foot fall and returning to display as if daring the earth to try again.

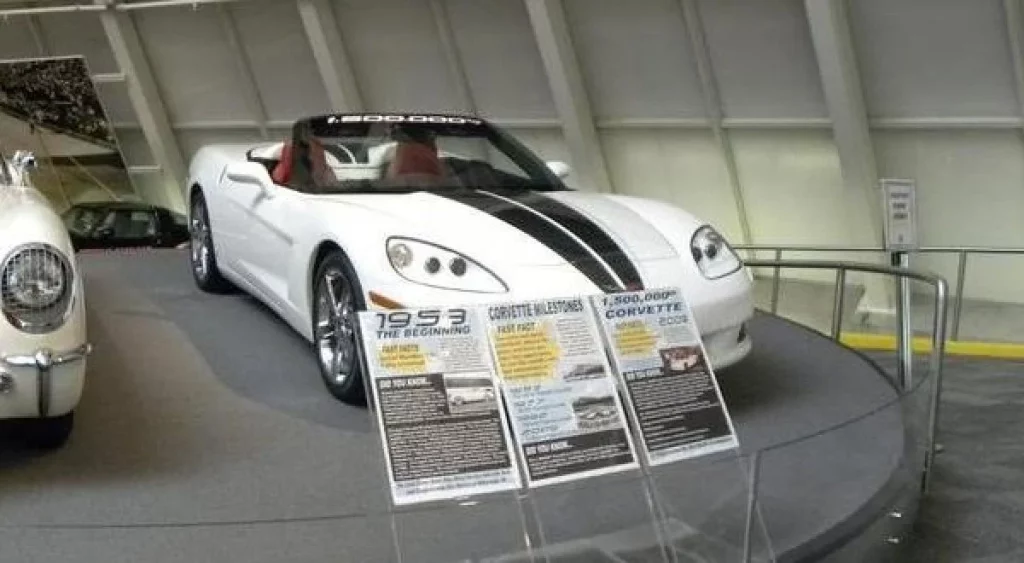

2) 2009 Corvette — The 1.5 Millionth

Like the One Millionth before it, the 1,500,000th Corvette was built to honor history. Completed in 2009 and finished in Arctic White with a red interior—again echoing the 1953 formula—it marked another production summit for America’s sports car. It wasn’t just a VIN milestone; it was a reminder that Corvette had survived oil embargoes, corporate shakeups, near-cancellations, and a bankruptcy-era General Motors to keep building. That context made its fall into the sinkhole especially jarring. This wasn’t just fiberglass and aluminum tumbling into limestone—it was a symbol of endurance taking a direct hit.

When the car was recovered, the damage was severe. Structural compromise, crushed bodywork, and the kind of distortion that makes a full restoration impractical without effectively replacing the car itself. In the end, the museum made a deliberate choice: leave it as-is. Today, the 1.5 Millionth is displayed in its recovered condition—scarred, broken, and honest. It stands not as a failure, but as documentation. A milestone car that now marks two moments in Corvette history instead of one.

3) 1993 Corvette — 40th Anniversary

The 1993 40th Anniversary Corvette, finished in Ruby Red Metallic with matching interior, carried a different kind of weight. Anniversary models are inherently reflective—they look backward while standing in the present. This particular car also came to the museum with personal history attached. It was donated with a story, with meaning beyond its option codes and paint designation. That’s part of what makes museum collections special: provenance matters.

The sinkhole did not spare sentiment. When the 40th Anniversary car was extracted, it was clear that restoration would require extraordinary intervention. The museum ultimately listed it among the five cars damaged beyond repair. Today, it remains unrestored, displayed in its post-collapse state. The once-deep Ruby finish now creased and fractured, it serves as a visual counterpoint to the pristine anniversary cars that surround it—a reminder that history is not always preserved in perfect condition.

4) 1962 Corvette — Tuxedo Black

The 1962 Corvette represented the end of the first generation—the final year of solid rear axles, the last chapter before independent rear suspension and the Sting Ray revolution. Finished in Tuxedo Black, it carried the quiet dignity of a classic that had already earned its place in the lineage. Unlike the milestone cars, it wasn’t about a production number. It was about stewardship—preserving the early DNA of the Corvette story.

Its fall into the sinkhole inflicted substantial damage, but not beyond salvation. The decision was made to restore it, and the process was comprehensive. Frame repair, panel replacement, mechanical rehabilitation—the kind of work that requires equal parts craftsmanship and reverence. When it was completed and reintroduced, the 1962 stood as proof that restoration, when done correctly, can honor authenticity rather than erase trauma. It is now back on display, not as a relic of collapse, but as a restored representative of Corvette’s formative years.

5) 1984 Corvette — PPG Pace Car

The 1984 PPG Pace Car is pure 1980s theater—bold graphics, aggressive aero treatments, high-visibility color. Built for the PPG Indy Car World Series and representing the rebirth of Corvette performance in the C4 era, it is a car that was never meant to be subtle. It is spectacle on wheels.

Ironically, spectacle made its fall even more dramatic. The car suffered catastrophic structural and cosmetic damage when the floor gave way. Given its complexity and the extent of destruction, restoration was deemed impractical. Today, it remains unrestored, preserved exactly as it emerged from the sinkhole. The once-vibrant bodywork now twisted and fractured, it feels less like a showpiece and more like an artifact from a crash site—an unfiltered snapshot of that February morning.

6) 1993 Corvette ZR-1 Spyder

The 1993 ZR-1 Spyder was never a production regular. A one-off conversion built as a showpiece, it combined the LT5-powered mystique of the ZR-1 with open-air drama. It was engineering bravado wrapped in early-1990s optimism—a car designed to make a statement.

The sinkhole made its own statement. The Spyder’s unique configuration did it no favors in the fall. When recovered, its damage was extensive and visually arresting. The museum chose preservation over restoration. Today, visitors can see the ZR-1 Spyder essentially as it came out of the hole—creased, collapsed, and undeniably real. It’s difficult to look at, and that’s precisely the point.

7) 2001 Corvette Z06 — Mallett Hammer

The Mallett Hammer Z06 was the outlaw of the group. An aftermarket monster built by Chuck Mallett, packing big horsepower and big attitude, it represented a different branch of Corvette culture—the tuner world, where factory performance is just a starting point. It also suffered one of the most violent landings in the collapse and was the final car recovered from the sinkhole.

When it came up, the damage was stark. Twisted frame sections, crushed composite panels, a stance that no suspension geometry chart could explain. Restoration would have meant rebuilding from the ground up—literally. The museum chose instead to preserve it in its mangled state. Today, it remains on display as perhaps the most visceral example of what the sinkhole did. It looks like gravity won. And in that moment, it did.

8) 2009 Corvette ZR1 — “Blue Devil”

The Blue Devil ZR1 was the halo car of the C6 generation—supercharged, carbon-fiber-laced, 638 horsepower of unapologetic American performance. It represented the outer edge of what Corvette could be in 2009. That’s part of why its survival story resonates so deeply.

As the first car extracted from the sinkhole—and the one that famously started and moved under its own power before a leak ended the brief drive—it became the emotional counterpunch to the disaster. General Motors committed to restoring it, and by fall 2014, the Blue Devil had been returned to factory-correct condition and publicly unveiled. Today, it stands as one of the great comeback stories in modern Corvette history: a flagship that fell 30 feet into limestone darkness and returned to the spotlight.

Why the Sinkhole Still Matters

Most museums preserve history by controlling it—lighting, signage, velvet ropes, climate systems, alarms. The sinkhole was the opposite. It was history intruding on the museum, uninvited, and leaving scars that couldn’t be airbrushed away.

And yet, the National Corvette Museum didn’t try to pretend it never happened. It chose the harder, more honest path: recover what could be saved, restore what deserved a second life, and preserve the rest as physical evidence that even icons live in the real world—built on real ground, subject to real forces.

Ultimately, the sinkhole became a Corvette story in the purest sense: impact, improvisation, engineering, resilience—and the decision to keep going.